Resources

INTELLIGENCE DIGEST

Abuse of file-sharing services aids phishing campaigns, yet again!

How free, legitimate file transfer services distribute malware via email

By Rodman Ramezanian - Enterprise Cloud Security Advisor

November 17, 2022 7 Minute Read

Email has been the lifeblood of enterprise communication and collaboration for decades; there’s simply no doubt about it. Email, however, is also still one of the most effective ways to distribute malware or ransomware, responsible for over 90% of malware deliveries and infections. This is despite the fact that email protection tools have improved and advanced over time.

Today, threat actors leverage free cloud tools, such as hosting providers, file transfer services, collaboration platforms, calendar organizers, or a combination of each, to bypass security measures and disseminate malicious payloads around the world. In this instance, we focus on the Lampion malware campaign, first reported by researchers at Cofense.

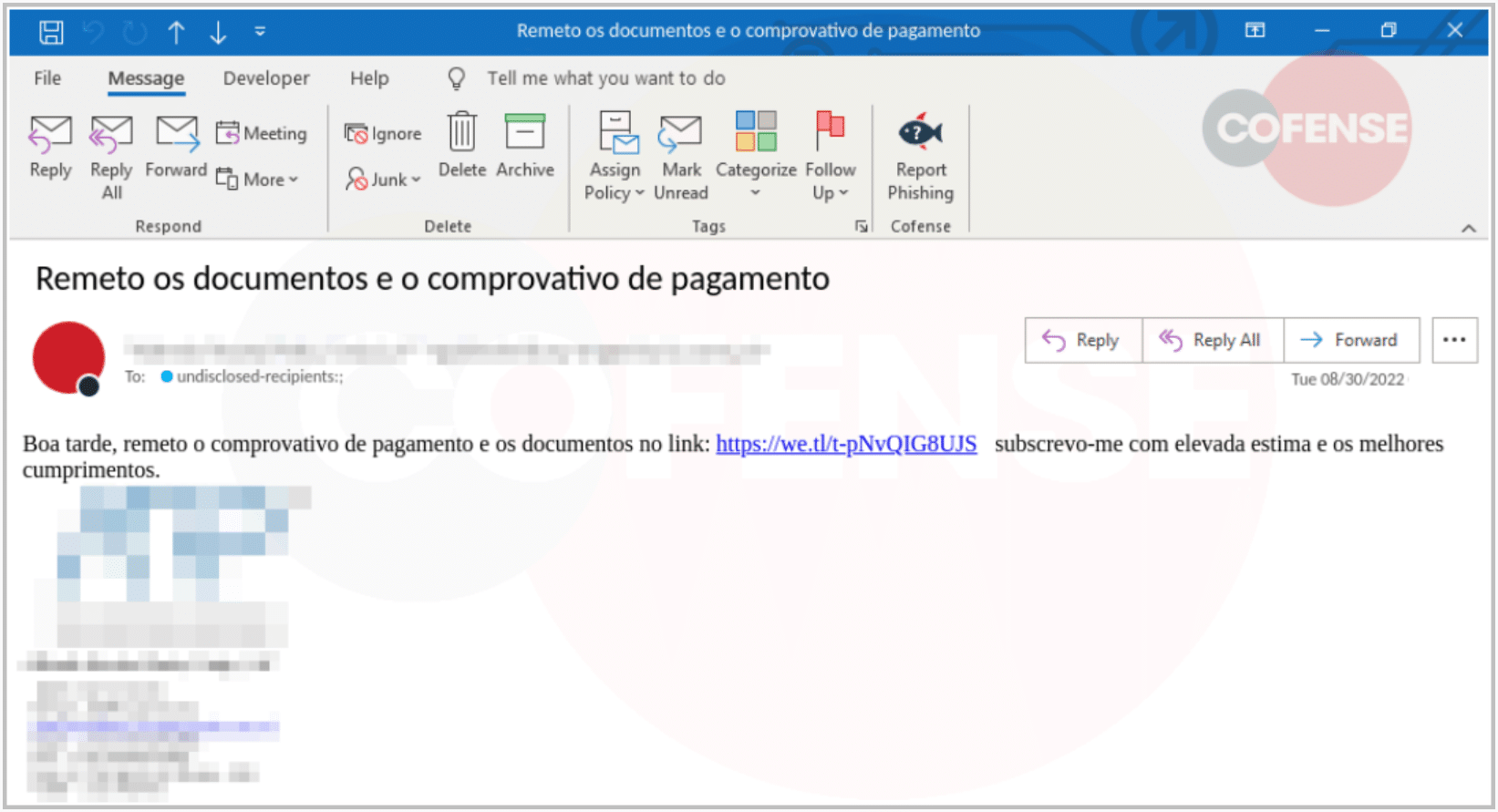

What makes this certain phishing campaign more threatening than most, is the use of a legitimate, and in most cases, implicitly trusted service named “WeTransfer”. For the unaware, WeTransfer offers free online file sharing services for users to upload/download content.

Lampion is a known threat strain, first observed back in 2019. In its infancy, it predominantly targeted Spanish demographics, but has since expanded operations across the globe. In 2022, however, researchers have noted an increase in circulation, with some detections exhibiting links to Bazaar and LockBit ransomware campaign hostnames.

The threat actors behind the Lampion malware campaign send phishing emails using hacked business accounts, encouraging end-users to download a ‘Proof of Payment’ mock file hosted on WeTransfer. Its primary objective is to extract bank account details from the system. The payload overlays its own login forms onto banking login pages. When users enter their credentials, these fake login forms will be stolen and sent back to the attacker.

Why do these breaches occur?

With email continuing to be such a vital artery for business operations, it’s no wonder why threat actors apply much of their attention there as one of the most successful vectors for payload delivery.

Then there’s, of course, phishing in its own right as a tactic, technique, and procedure. We, humans, continue to be considered “the weakest links” in cybersecurity, falling for convincing decoys and social engineering lures. Verizon recently backed this trend in their 2022 Data Breach Investigations Report, stating that 82% of breaches are at the hands of humans.

This form of malware is particularly challenging for banking security teams, as the accessing of malicious links are performed through the victim’s system — a trusted device. What’s more, WeTransfer is not the only legitimate service the attackers are using/abusing – they’re also leveraging Amazon Web Services (AWS) resources to host payloads.

Another difficulty lies in the fact that conventional reputational checks performed by security tools may not always be prove to be effective. WeTransfer, as a somewhat-reputable, genuine service, and seemingly-generic AWS-hosted addresses may not necessarily sound off any alarms; at least reputationally on most, if not all, vendor reputation databases.

For this reason, a different, more innovative approach must be considered.

What can be done?

Given these types of threats rely, and thrive on use of external URLs to introduce the payload, remote browser isolation proves to be one of the most effective ways to prevent victim systems from navigating directly to the attacker’s intended content.

Through this method, in the unfortunate event that a victim clicks on a malicious link – i.e. the crafty WeTransfer link in this scenario – a remotely isolated browser session would instantly kick-in to shield the system from any of the forthcoming contents.

How, you ask?

Either based on risky reputational categories (e.g. File Sharing, Peer2Peer, Gambling, etc), URL category, IP address, Domain, or even by matches according to custom created lists, security teams can ensure that if/when their users fall victim to a similar attack, none of the malicious contents from that browser session will ever reach the local device itself – only a visual stream of pixels representing the page

Users can still interact with the site as per normal (as per admin discretion), or they can have functions such as uploads, downloads, clipboard usage, and others blocked entirely. But in this way, the remotely isolated browser session displaying the page shields any of the malicious payloads, cookies, and content from the user and their device.

In doing so, security teams are no longer at the whim of reputational lookups or binary allow/deny policies to spot the wolf in sheep’s clothing.

Use Skyhigh Security?

- Enable activity monitoring, data loss prevention, and threat protection for GitHub

- Monitor GitHub user activity in the Activity Monitoring page

- Block access to URLs based on reputation and domain categorization

- Block URLs in Forbidden Categories such as File Sharing Sites

- Protect against Uncategorized Websites and specific Media Types

- Apply insights from URL reputations for Anti-malware Filtering

With over 11 years’ worth of extensive cybersecurity industry experience, Rodman Ramezanian is an Enterprise Cloud Security Advisor, responsible for Technical Advisory, Enablement, Solution Design and Architecture at Skyhigh Security. In this role, Rodman primarily focuses on Australian Federal Government, Defense, and Enterprise organizations.

Rodman specializes in the areas of Adversarial Threat Intelligence, Cyber Crime, Data Protection, and Cloud Security. He is an Australian Signals Directorate (ASD)-endorsed IRAP Assessor – currently holding CISSP, CCSP, CISA, CDPSE, Microsoft Azure, and MITRE ATT&CK CTI certifications.

Candidly, Rodman has a strong passion for articulating complex matters in simple terms, helping the average person and new security professionals understand the what, why, and how of cybersecurity.

Attack Highlights

- Targeted users receive a ZIP package containing a VBS (Virtual Basic Script).

- The attack begins once the user executes the script file, and a WScript process starts, which generates four additional VBS files with random names.

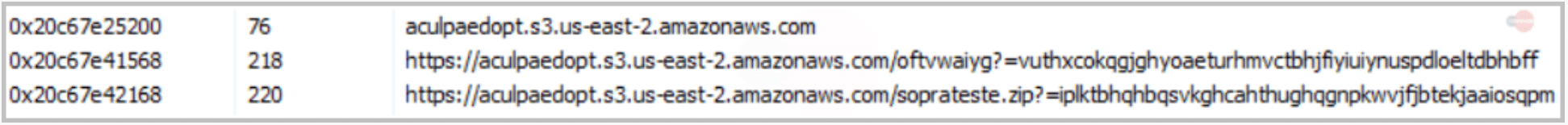

- The WScript process retrieves DLL files using URLs with references to AWS instances.

- Once downloaded, the DLL payloads are loaded into memory.

- From there, Lampion runs and maintains persistence discreetly on compromised systems, before beginning to search for and exfiltrate data on the system.

- Commanded by a remote C2 server, the trojan mimics a login form over the original login page, so when a user enters his credentials, the fake form will send the details to the hacker.

- Actors behind Lampion consistently update their payloads with additional layers and bogus code to render it more difficult to detect by scanners.